The Ipswichian Interglacial

The greatest and the warmest interglacial stage during the whole of the Ice Age was the Ipswichian, about 120,000 years ago. This period must have been warmer than the present day with monkeys, elephants and lions in southern England, the bones of which were found beneath Trafalgar Square in the 1950s as a result of building excavations. Downstream, the foreshore at East Mersea is currently one of the best sites of Ipswichian age in Britain. Here there are highly fossiliferous sediments called ‘hippo gravels’, so called because the hippopotamus was remarkably abundant in our region at this time, but curiously absent during almost all of the other interglacial stages. Fossils indicate that humans and also animals such as the horse were absent from Britain during the Ipswichian. Each interglacial stage has a distinctive fauna, presumably because, in each case, some animals were not quick enough to migrate north as the climate improved and were halted by the reappearance of the English Channel as sea level rose.

The Most Recent Glaciation

Following the warmth of the Ipswichian came the intense cold of the Devensian stage when an ice sheet again spread south but this time reaching no further than north Norfolk. Permafrost conditions gripped this region, providing home for reindeer, arctic wolf and similar species. Fossils of these animals have been found in a gravel pit at Great Totham and further west in the Lea valley.

Perhaps the most spectacular evidence of the Devensian cold stage is the network of ice wedge polygons that are occasionally revealed by crop marks in fields during hot, dry summers. Ice wedges are formed when the frozen ground shrinks and cracks during times of extreme cold. Each summer the cracks filled with water which then froze the following winter widening the cracks; a process that continued for thousands of years. At the end of the glacial stage the crack filled with debris preserving them as ice wedge casts, which are now revealed as crop marks.

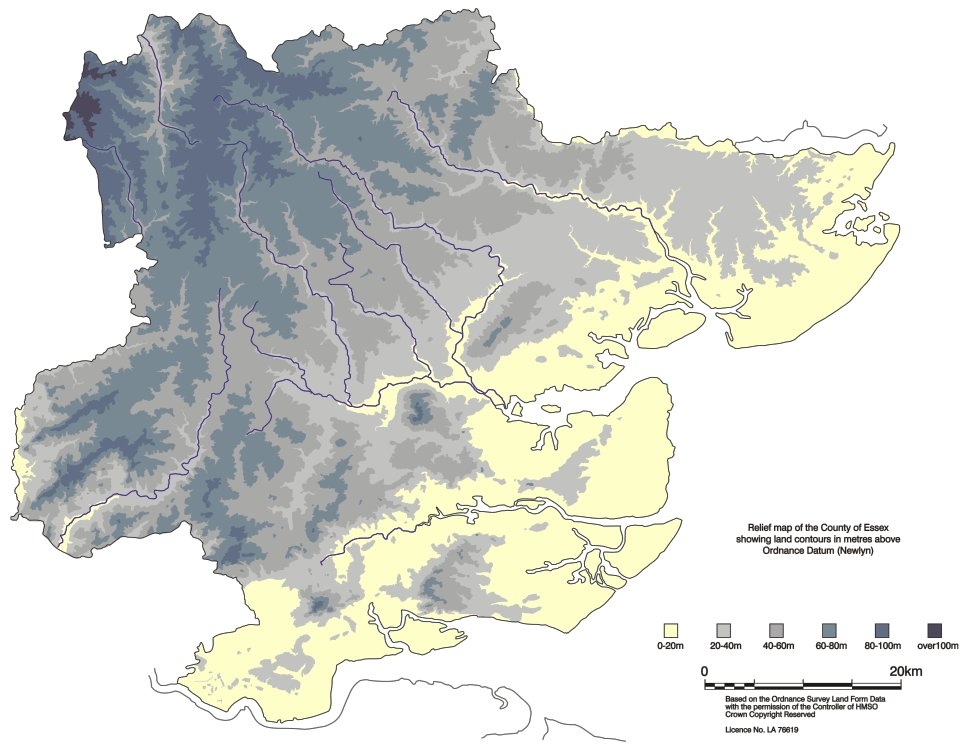

The Landscape Today

Soils

Soil is the uppermost layer of the Earth’s surface and is immensely important for life on Earth. It is a mixture of weathered rock fragments and minerals, living organisms, and decaying organic matter called humus, and is the product of several complex and interacting processes. Soil is formed over a long period of time. There are many types of soil, each one reflecting the influence of climate, relief and the underlying geology, as well as the chemical and biological processes involved. Soils are classified according to the national system of the Soil Survey of England and Wales.

The soil types of Essex have helped shape the landscape, wildlife and economy of the County. The boulder clay region of north-west and central Essex has soils which are a rich, crop-producing resource. The London Clay gives rise to less fertile soil and its heavy nature has made arable farming difficult leading to small, dispersed settlements, and an emphasis on pasture. However, the extensive brickearth that overlies the London Clay to the north and east of Colchester form a rich, fertle soil suited particularly to market gardening. Soils developed on the Bagshot Hills, such as the Epping Forest Ridge, are extremely complex with mixed hornbeam/oak woodland on the London Clay and beech on the Claygate Beds.

This brief account of Essex soils is summarised from The Essex Environment: A Report on the State of the County’s Environment published by Essex County Council (1992). A good introduction to the soils of Essex can be found in a comprehensive report for Essex produced in 2003 as part of English Heritage’s National Mapping Programme (NMP).