The Chalk Sea

Chalk is effectively the starting point of our geological story as it is the oldest rock exposed at the surface in our county. Chalk also forms the foundations of the London Basin, a large basin-shaped structure beneath London and Essex. A great thickness of chalk forms the Chiltern Hills and their continuation as the hills of south Cambridgeshire; it then passes beneath central London and Essex and comes to the surface again as the North Downs of Surrey and Kent. This layer was originally horizontal, having been laid down as a limy mud on the floor of a tropical sea during the age of the dinosaurs; the folding occurring millions of years later as Britain was squeezed as a result of the African continent pushing into Europe and creating the Alps.

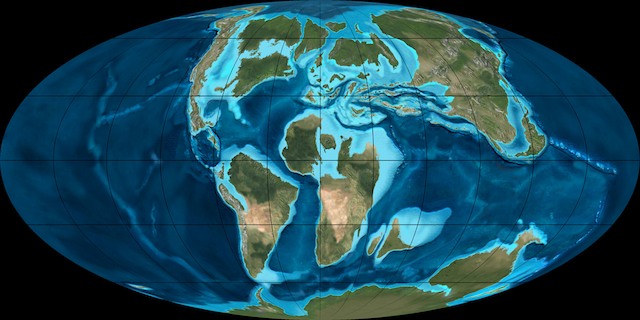

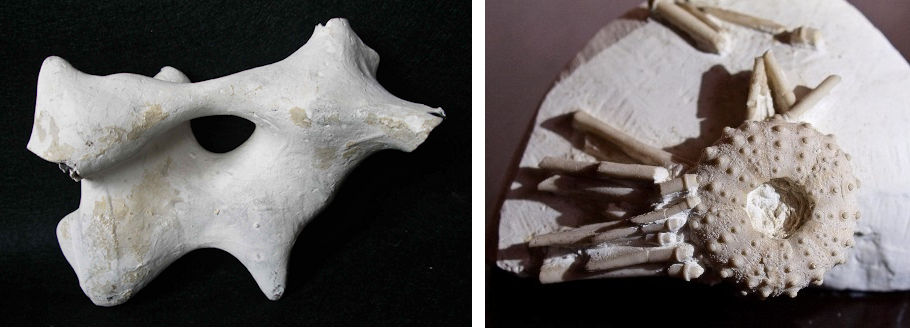

The Chalk Sea was in existence between 80 and 100 million years ago (during the Cretaceous period) and the purity of the chalk means that the water must have been crystal clear and the nearest land a considerable distance away; in fact it is thought that this sea may have covered most of northern Europe. The chalk sea was teeming with marine life such as molluscs, sponges, corals, sea urchins and fish, and at the top of the food chain were the mosasaurs, giant marine reptiles up to 10 metres long with a long body and tail, paddle-like limbs and heavy jaws armed with sharp, conical teeth.

The smallest creatures were microscopic marine algae with protective shells called coccoliths, that accumulated on the sea floor in their billions. In fact it is now realised that chalk is almost entirely made up of these tiny fragmented shells which are only visible under an electron microscope.

Chalk contains numerous nodules of flint, a variety of quartz formed as nodules in the mud on the chalk sea floor. The nodules were mostly formed by the infilling of burrows made by sea creatures in the white mud. As a result, they can be remarkable shapes, often with horns or spiky protrusions.

Chalk can be seen in the south of the county in Thurrock where there are many giant quarries, the remnants of the Portland cement industry. Typical of these quarries is Grays Chalk Quarry, which is a nature reserve, managed by the Essex Wildlife Trust. On the northern limb of the London Basin is Saffron Walden which also has disused chalk quarries but on a much smaller scale, and most of these are rapidly disappearing as a result of development and landfill.