The Oldest Rocks

The geological story of Essex starts with rocks that are between 440 and 360 million years old. Dating from the Silurian and Devonian periods (part of the Palaeozoic era), these rocks consist of hard, slaty shales, mudstones and sandstones and are over 300 metres (1,000 feet) below the surface. They have been encountered in boreholes at several places in Essex and they represent a time in the distant past when the first animals were leaving the sea to colonise the land. Similar rocks can be seen at the surface in the Welsh Borderland.

Lying on top of these ancient rocks is the Gault, a marly clay from a muddy sea that dates from the middle of the Cretaceous period, about 100 million years ago. This means that, beneath Essex, there is a gap in the geological record that represents about 250 million years and includes the Triassic, Jurassic and early Cretaceous periods. After deposition of the Gault, sand spread into this sea to form a deposit called the Upper Greensand. At this time sea levels were rising leading to flooding of the continents, the conditions under which the next rock was formed – the Chalk.

A Buried Landscape

The Gault Clay was laid down when the sea flooded south-east England in the mid Cretaceous period about 100 million years ago. The land that was inundated consisted of rocks dating from the Palaeozoic era (rocks from the Devonian period in what is now south Essex and from the Silurian period in north-east Essex). This ancient, buried land surface still exists beneath our feet and has been encountered in the boreholes at Harwich, Weeley, Fobbing, Beckton and Canvey Island.

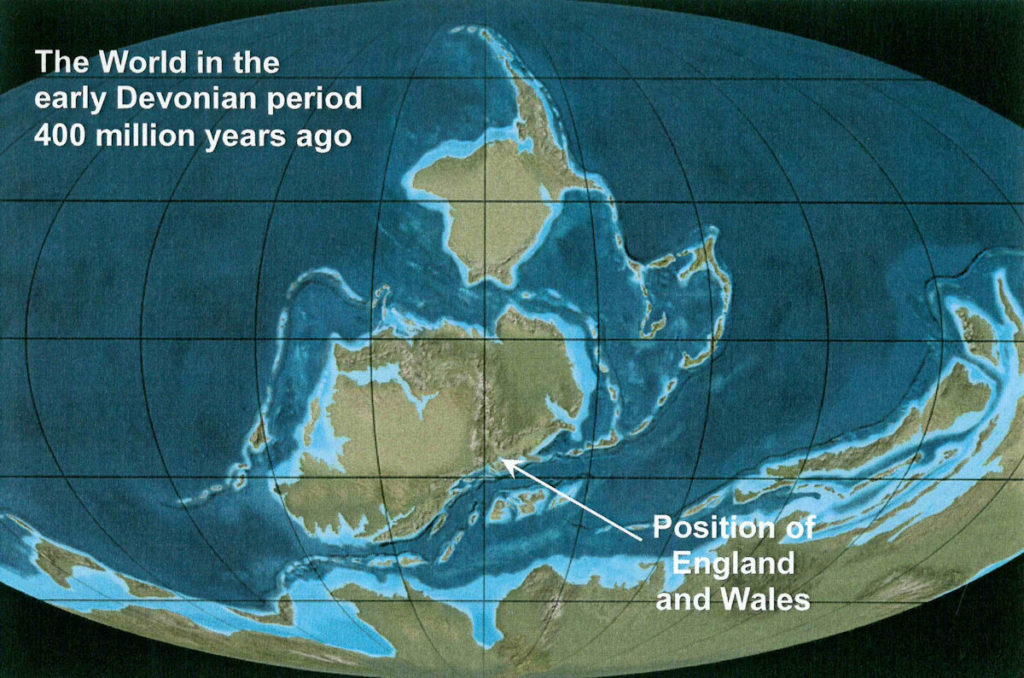

During the Palaeozoic era the Earth was a very different place. In the early Devonian period, for example (see map below), Britain was situated south of the equator and was part of a large landmass known as Laurussia (also known as Euramerica or the “Old Red Sandstone” continent). Laurussia was made up of present-day North America, Western Europe through the Urals, and Balto-Scandinavia. To the south can be seen the giant continent of Gondwana which is straddling the South Pole.

The Essex Earthquake

Although it is generally thought that earthquakes are rare in Britain they do in fact occur quite frequently. Approximately 300 are detected each year by sophisticated monitoring equipment and of these about 30 are strong enough to be felt. Occasionally, however, Britain is shaken by an earthquake which causes structural damage.

The most destructive earthquake ever recorded in Britain occurred in Essex on the morning of 22 April 1884 and strongly shook most of the county. It is known as the Colchester earthquake because the greatest damage was caused to Colchester, Wivenhoe and the towns and villages nearby. The tremor was felt over much of southern England and parts of France and Belgium, and its magnitude has been estimated at 5.2 on the Richter scale. The number of casualties is difficult to estimate, but it is doubtful whether any deaths or serious injuries can be attributed to the earthquake. The earthquake was probably due to movement along a fault in the ancient Palaeozoic rocks under Essex which would have affected the overlying cover of Cretaceous and Tertiary strata.

An extensive study of the effects of the earthquake was carried out shortly afterwards by the Essex Field Club and their detailed report, published in 1885, is a fascinating and extremely valuable account. Copies of the report are available for reference at Colchester and Chelmsford libraries.