The Ice Age – Cooling of the Planet

The ‘icing’ on the county’s geological ‘cake’ is the remarkable variety of deposits laid down during the Ice Age.

The story of the Ice Age starts around two million years ago. At this time the climate was probably not too dissimilar to the present day but the temperature had been slowly dropping for tens of millions of years, ever since the balmy, tropical days of the dinosaurs. The oldest Ice Age deposit in our region was laid down in a shallow sea and is known as the Chillesford Sand (part of the Norwich Crag Formation). This sand occurs at the base of gravel pits in north-west Essex but it is extremely difficult to date due to the absence of fossils for much of its thickness. Following deposition of the Chillesford Sand there is a very fragmentary record of our climate and landscape over the next million years or so. This period, which makes up most of the early part of the Ice Age, is poorly understood but some evidence has been preserved, thanks largely to an early route of the River Thames.

The Early Thames

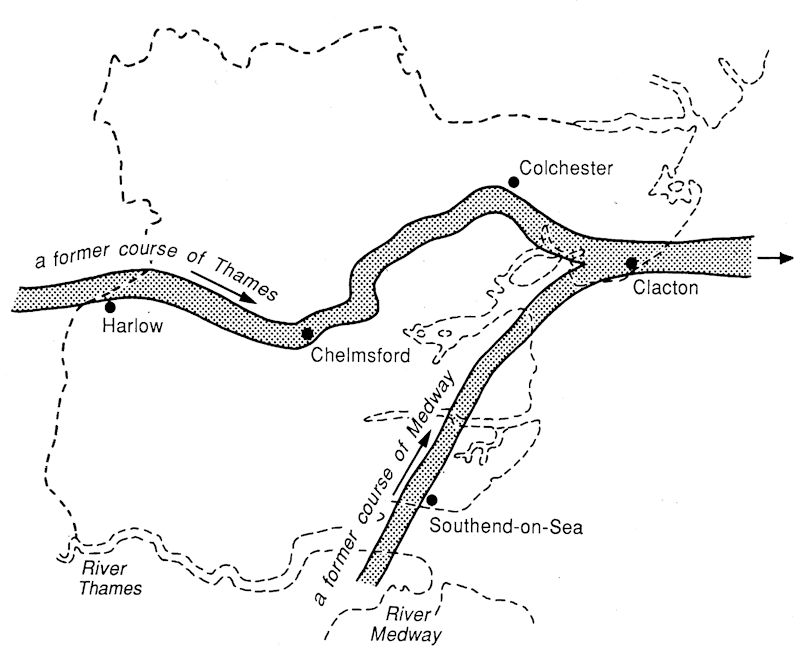

During the early Ice Age the Thames flowed to the north of London, through north Essex, Suffolk and Norfolk and out across what is now the southern North Sea to become a tributary of the Rhine; the evidence for this being a substantial thickness of what is called Kesgrave Sands and Gravels which, remarkably, represents the actual bed of the river. These old Thames gravels contain a variety of unusual pebbles from as far away as North Wales, proving that, at that time, the Thames, and its tributaries, must have been a huge river system draining the Welsh mountains and bringing their characteristic volcanic rocks into the Thames basin.

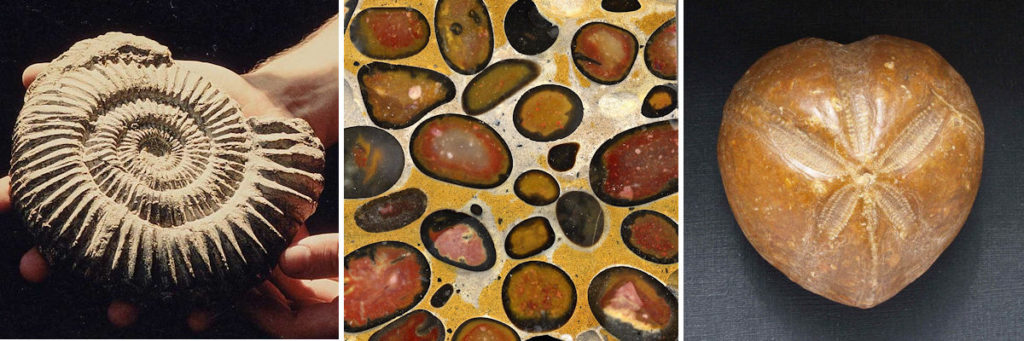

The gravels also contain large boulders of puddingstone and sarsens, which are very hard conglomerates and sandstones respectively. They are believed to be derived from pebble and sand seams in the Reading Beds, and which have subsequently become cemented by quartz. They have been put to use by man as ancient way markers at road junctions. The gravels have great commercial value and are worked in numerous gravel pits between Harlow, Chelmsford and Colchester, which was the route of the Thames over 450,000 years ago.

During this time the River Medway flowed north across east Essex to join the Thames near Clacton, leaving behind a ribbon of distinctive gravel which can be found between Burnham-on-Crouch and Bradwell-on-Sea. There were also other northward-flowing tributaries of the early Thames. Evidence of these are the patches of gravel that are found on the tops of the hills in south Essex, such as the Langdon Hills, Warley and High Beach in Epping Forest.

The Anglian Ice Sheet

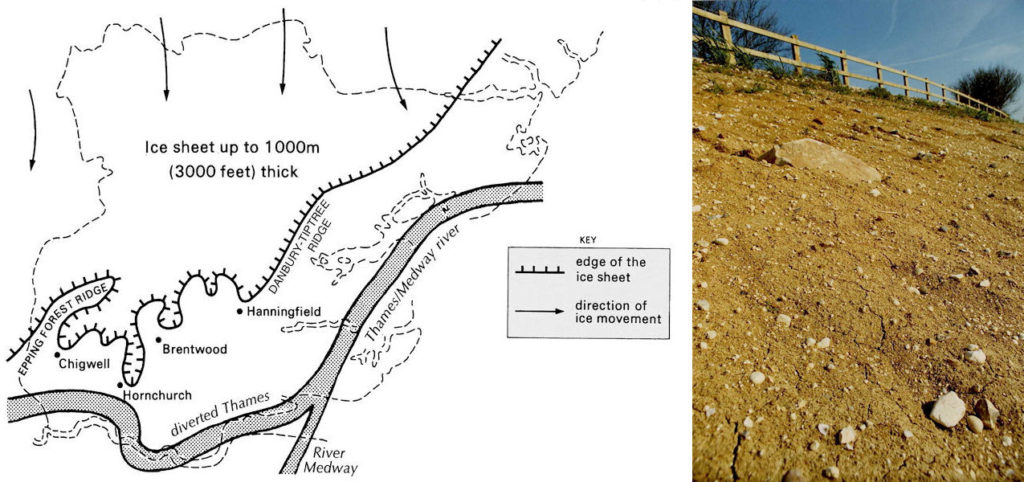

The regular pulses of climate change culminated in the Anglian glaciation, a severe cold stage about 450,000 years ago that allowed a great ice sheet to spread south into the region across the valley of the early Thames. A lobe of ice from this ice sheet blocked the Thames in the Vale of St. Albans causing a catastrophic change to the route of the river, diverting it south to its present position.

Evidence for the existence of this ice sheet is a substantial thickness of boulder clay, or till, left behind by the ice as it ground southwards across the frozen landscape. The boulder clay, lying on top of the old Thames gravels, forms a distinct plateau over the north of Essex, now dissected by modern river valleys. Boulder clay can be found as far south as Hornchurch, which is known as the most southerly point in England that the ice penetrated during the whole of the Ice Age. The boulder clay contains rocks, called glacial erratics, that have been carried south by the ice, some of them from as far away as northern England and Scotland. The boulder clay also contains some fossils such as Jurassic ammonites and belemnites, brought here from the Midlands.

The landscape at this time is almost impossible for us to visualise. As the region was situated at the southern-most limit of the Anglian ice sheet, colossal volumes of melt water would have been continually released and the evidence for this is also preserved beneath our feet. In parts of East Anglia, boreholes have revealed deep, steep-sided valleys cut into the chalk bedrock and now completely filled with sand and gravel and hidden by a covering of boulder clay. Known as buried tunnel valleys or buried channels these remarkable natural features were formed beneath the ice sheet and were the main drainage routes for melt water. One of the best examples of a buried channel is the Cam-Stort Buried Channel that is present from Great Chesterford south as far as Bishops Stortford. You can’t see it but in Newport it passes beneath your feet and is some 100 metres (300 feet) deep, almost half of this depth being below present sea level. Glacial gravel is present in many other places in Essex. It is recognisable as an unsorted residue of many rock types, mostly flint, laid down under these exceptional conditions.